Rock and Gem Magazine Article

Gemstones of the Beaches

Gemstones of the Beaches

May 2009 Rock And Gem Magazine

Article by Steve Voynick

Photos by Linda Jereb - By The Sea Jewelry

Interest In Sea Glass Is Booming

While growing up meant the Jersey Shore, I spent many hours combing the beaches for shells, driftwood and especially sea glass - bits of glass that the tides and sand had tumbled, rounded and frosted into what reminded me of gemstones. I imagined the clear pieces as diamonds, the greens as emeralds, and so on. Some days I would find only a single piece, but on days after a storm had "turned" the beach, I could find a dozen.

Because sea glass was just a novelty then, I relegated my collection to a coffee can tucked away in a corner of the garage. Years later when I left home for college, one of the many things I gave away was that can filled with sea glass. That has proved to be a mistake.

Today, sea glass is the foundation of a booming business, with a legion of collectors, a national trade organization, a well attended annual show, growing numbers of sea glass jewelry makers, and a network of dealers on the Atlantic, Pacific and Gulf coasts and the shores of the Great Lakes.

"Sea glass has never been more popular" says Linda Jereb of Sebastian Florida, proprietor of By The Sea Jewelry, the leading Internet retailer of sea glass and fine sea glass jewelry. "Interest took off in the 1990's after the public learned to appreciate the unique beauty, origin and history of sea glass, and accepted is as a gem-like souvenir of oceans and beaches"

Jereb, who is trained in commercial art and graphics and had a background in sales and marketing, was raised in Pennsylvania where there was no sea glass to collect. Instead, she became interested in minerals and gemstones, which she collected at nearby sites. Although she occasionally searched for Cape May "diamonds" (rounded pieces of clear quartz) on the beaches of Cape May New Jersey, she didn't learn about sea glass until she moved to North Carolina's Outer Banks in the late 1980's.

"A friend showed me some sea glass that she had just found" Jereb remembers, "I was intrigued with the gem-like, frosted colors and started collecting it for myself".

Jereb next began making sea glass jewelry using simple copper wire wraps. Slowly building a business, she moved on to gold and silver wire wraps in original designs that best display the unique qualities of sea glass. Then in the early 1990's, she took her business online as the nations first Internet source for sea glass jewelry./

"Sea glass was still just a novelty then" Jereb recalls. "Although shore residents had collected sea glass for generations, it was hardly known beyond the beaches. But magazines began running a few sea glass articles and the growing numbers of beach visitors became attracted to higher quality sea glass jewelry. By the late 1990's, interest in sea glass collecting and jewelry had taken off".

In 2000, Jereb did her part to further the attention by discussing sea glass on the NBC TV's "Later Today" show.

Sea glass, also known as "ocean glass", "beach glass", "drift glass" and "mermaids tears" originates mainly from bottles, jars, vials and other glass containers that were discarded as litter or otherwise ended up in the sea. Lesser amounts come from shipwreck glass, industrial debris, glass fishing floats and automobile headlights and tail lights (mostly form automobiles used to build artificial reefs). After this glass had fragmented, it becomes rounded and frosted by sand that is churned by waves and storms and gently shifted by littoral (coastal) currents.

Glass fragments transform into sea glass in a two part process of physical and chemical change. Physical alteration occurs when the turbulent surf and sand environment abrades the surface of the glass. The rounded edges and delicate surface frosting that are characteristic of fine pieces of sea glass are possible because of the generally similar hardness of the glass and quartz sand.

Most beach sand consists primarily of bits of quartz (silicon dioxide). Of the major rock forming minerals, quartz is the most abundant and durable and the Mohs 2, the hardest. During the physical and chemical weathering of rocks and feldspar's, mica's and other important rock forming minerals, all of which are considerably softer than quartz, either alter into clays or are ground into microscopic bits. Quartz however, survives as sand.

The creation of sea glass is possible because glass is only slightly softer than quartz. Most modern glass - that is, glass manufactured withing the last century - has a hardness of Mohs 5.5 to 6, a bit less than that of quartz. When fragments become part of the beach alluvial, they are in essence placed withing a giant, very low speed tumbling machine loaded with quartz sand grit. If glass were somewhat harder than quartz, its fragments might become only slightly abraded rather than well rounded and frosted. Conversely, if glass were much softer than quartz, it would be quickly worn to bits, leaving very little sea glass to collect.

This process of physical abrasion is aided by the chemical deterioration that occurs when glass is subject to long term immersion in sea water. Most sea glass is originates from soda line glass, and inexpensive mass manufactured material used for bottles, tableware, and window plate glass. Soda-lime glass consists mainly of noncrystalline silica (silicon dioxide). It also contains such alkali fluxes as sodium and potassium carbonates, which enhances work ability by lowering fusion temperature and decreasing viscosity, along with calcium and magnesium carbonates, which stabilize the molten glass mixtures.

During the long term immersion in sea water, two things occur to the surface of the glass. First, the saline seawater leaches out some of the sodium and calcium. Then the glass surface becomes hydrated as water molecules replace the leached sodium and calcium carbonate molecules. This slightly softens the glass surface and accelerates the abrasion process that rounds and frosts the glass.

Just how long it takes for a sea sand environment to transform fragments into sea glass is uncertain, but at least several decades are needed to produce nicely rounded and frosted pieces. The time necessary to create glass varies considerably with conditions. Beach sand subjected to strong littoral currents or frequent storms will scour glass fragments into sea glass much more rabidly than will sand from calmer and more protected beaches.

Every piece of sea glass has a time "window" during which it can be collected. Glass fragments with too little time in the sea-sand environment retain sharp edges and smooth surface areas. These lack the visual and tactile appeal of true sea glass and look more like slightly abraded glass letter,. On the other hand, glass with too much time in tide and sand can become too small or too thing to be valuable.

The quality and depth of sea glass frosting does not necessarily indicate the length of time that the piece of glass has spent in the sea- sand environment. While turbulent environments can frost glass relatively quickly, even long periods of immersion in fresh or brackish water or calmer environments can produce only light frosting.

Sea glass has local origins and is rarely found more than a few miles from where the glass fragmented. Travel distances vary with the rate of particulate transport, that is, how quickly the prevailing local littoral currents shift the beach sad debris.

Although individual pieces do not travel far, sea glass can nevertheless be found virtually anywhere, As beachcombers who have searched remote beaches will testify, bottles, jars and glass fishing floats - the "raw materials" of sea glass, can drift for thousands of miles before fragmenting and eventually becoming sea glass.

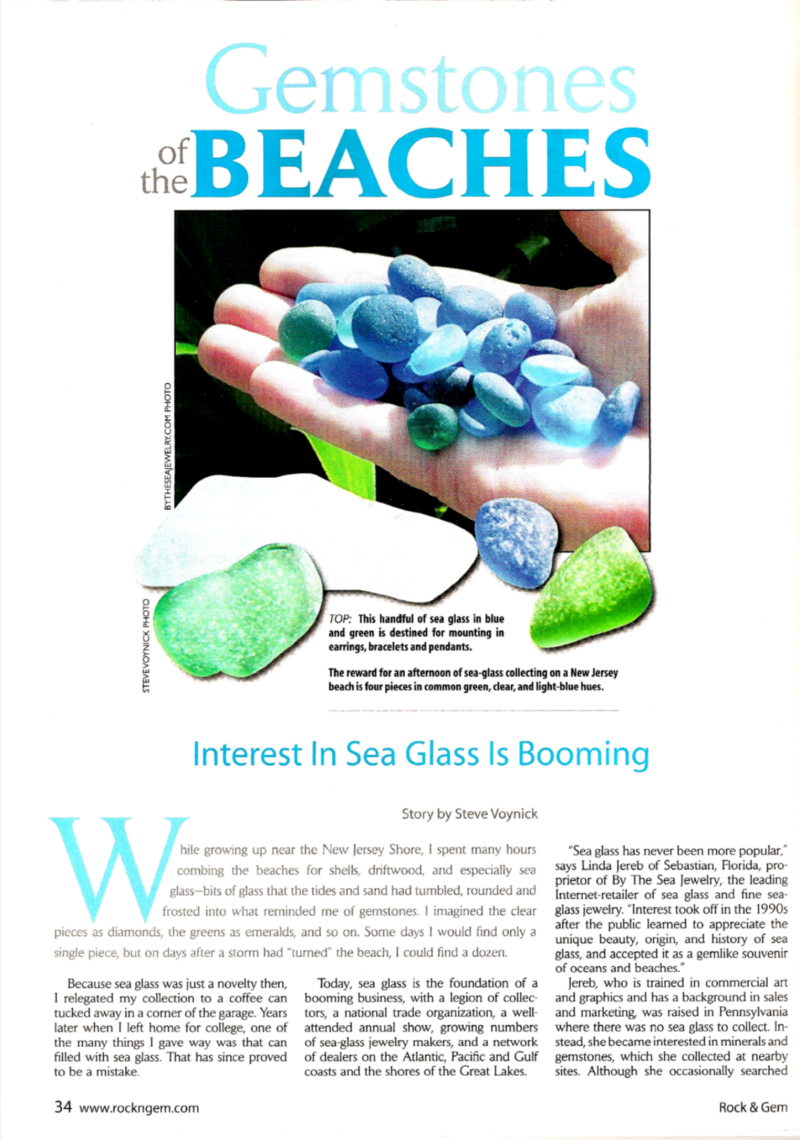

In her studio at By The Sea Jewelry, Jereb grades individual pieces of sea glass using three primary criteria: color, frosting and quality, and individuality of thickness and shape. Not surprisingly, the most abundant sea glass colors are those found in the mass manufactured bottle glass used as containers for beer, wine soft drinks and an array of food and household products - "common brown", "common green", and clear (or frosted to whiteness). Jereb estimates that roughly 40 percent of sea glass is clear or white, somewhat less than 40 percent is common browns and about 20 percent is green.

The less plentiful colors, such as the olives, amber's and pale greens that originate from older glass bottles, are more interesting and valuable. After these come the attractive blues, lavenders, bight seafoam greens, and other unusual shades of green. The rarest of colors are red, pink, peach, opaque white, vivid aqua, lime and jadeite green, and orange. Peach colors usually come from Depression glass while the opaque whites and jadeite's greens are from tableware.

Jereb estimates that five in every 100 pieces of sea glass a a light seafoam green, the remains of old Coca-Cola TM bottles. Just one in 250 is dark "cobalt" blue that is usually a fragment of and old medicine bottle. Only one in 400 is lavender, a delicate color produced by ling term exposure of clear glass that the ultraviolet component of sunlight. Finally one if 500 is line green, and only one is 600 is cornflower blue.

"In the very rare colors, one in 1,000 pieces is deep aqua or turquoise, one in 5,000 is ruby red, and only one in 10,000 is a brilliant red or orange". Jereb estimates. "I've personally collected about 600 pounds of sea glass. Of these tens of thousands of pieces, only a few were red or orange.

The rarest colors usually originate as decorative housewares glass. Interestingly, bright red glass was originally make by incorporating traces of metallic gold into the glass mix, but since the 1950's, glass makers have used copper to create red glass.

Black or near black is another rare color. Al ought much glass manufactured before 1850 was black, long periods of immersion and abrasion, combined with crude compositions and resultant susceptibility to accelerated chemical decomposition, have left relatively little to collect.

While colors are intriguing, frosting is what really distinguishes sea glass from "litter" glass. Unlike the smooth cold, hard, vitreous luster of unaltered glass, the surface of well frosted sea glass has a warm appealing look, as well as unusual pleasing tactile qualities that collectors describe as "soft" and "calming".

Sea glass frosted is also graded. The least desirable pieces are those that have not made the full transition from litter glass to sea glass. These are only lightly frosted and exhibit share edges, nicks and residual shiny sections. Veteran sea glass collectors leaves these pieces behind to let the sea finish its work. The most desirable sea glass has rounded edges, no nicks, and a deep, even frosting that bears no resemblance to the original vitreous glass surface.

The final factor that determines sea glass value is unusual characteristics such as exceptional thickness, odd shapes (often from bottle bases or necks), embossing and bubble inclusions in very old glass. Other interesting forms include "bonfire" glass that has been partially melted in fires, marbles of the type once used as sailing ship ballast, and frosted trinkets, figurines and bottle stoppers.

What is the monetary value of sea glass? As with any gem like material, the bottom line is whatever the market will bear at a given time, but on average, sea glass prices have risen steadily for 15 years. When Jereb started out in business, a pound of sea glass in common color cost less than $15. Today the same amount sells for $40. Prices of "gem-quality" sea glass suitable for use in jewelry, especially in unusual colors, have risen more more. Well frosted pieces in the rare, bright shakes of red or orange can now sell for more than $200 each. Recently an exceptionally large piece of bright aqua sea glass sold for $260.

When sea glass began to increase in value and popularity, books about the collectible began to appear, as did imitations. Recent titles include Richard Lamotte's Pure Sea Glass:Discovering natures Vanishing Gems (Sea Glass Publishing 2004) and Carole Lambert's Sea Glass Chronicles: Whispers from the Past (Down East Books 2001) and Passion For Sea Glass (Down East Books 2008). While these books have helped to promote the image of sea glass, the imitations have not.

"The imitations are a problem" Jereb says. "About five years ago when the prices were rising rapidly, imitation sea glass, which is correctly called "craft glass", began appearing on the market. Much was moved thought the auctions Web sites where buyers were often unaware that they were paying genuine sea glass prices for imitation material.

Craft glass is produced in tow ways: by placing glass fragments in lapidary tumblers loaded with coarse grit and water mixes for a few days, and by chemically etching glass fragments in baths of hydrofluoric acid. Both processes are quick and inexpensive, and produce unlimited quantities of craft glass. Also, because fragments of brightly colored stained glass are often used as starting materials, craft glass is readily available in colors that would be very rare and valuable in genuine sea glass.

Experts however, can visually distinguish craft glass from the genuine item. Under magnification, the frosted surface of genuine sea glass shows uneven random patterns of the "pores" that resemble small "C" shaped abrasions. These are tiny indention's from which conchoidal chips have been flaked from the glass surface by the pressure of shifting sand in a surf environment. The frosting in tumble craft glass however, because of the uniformity of grit size and the absence of any significant tumbler pressure, is even and has no conchoidal indention. In chemically etched craft glass, the frosting texture is very uniform and fine grained, and pieces retain the sharp edges. Both types of craft glass show no curvature or variation of thickness.

"These imitations have created a disclosure issue identical to that in synthetic gemstone marketing" says Jereb. "There is nothing wrong with either synthetic gemstones or craft glass, provided that this is full disclosure of origin.

"Genuine sea glass is very unusual" she continues, "It h as rarity, a sense of romance, history, and intrigue - elements that derive from the sea and beaches, not from tumblers and acid baths. Many collectors are even interested in the archaeological aspects of sea glass, and attempt to date it by color, inclusions, shapes and the localities where it was found. I call sea glass a 'reverse gemstone'. Unlike natural gemstones that we facet into gems, sea glass is a man-made material that nature fashions into a gemstone.

Jereb who has recently studied the fabrication of traditional silver settings with a master jeweler, sells her sea glass jewelry under the name "Genuine Sea Glass" which she trademarked in 1991. Her jewelry line consists of earring, bracelets and pendants that display wire wrapped or drilled sea glass. In her designs, Jereb leaves as much of the glass as possible uncovered so that its wearer may easily experience the unique sensation of touching it. She also buys and sells genuine sea glass in lots of more than 100 pieces, along with "speculum glass", individual pieces of genuine sea glass that are too large for jewelry, but make eye catching displays.

Jereb also sells (Discontinued) a line of "Fanta Sea Glass TM". "We're very upfront about the origin of our Fanta Sea Glass and clearly identify it as artificially made," Jereb explains. "Craft glass fills a niche in the market by providing buyers with an easily affordable alternative to the increasing prices of genuine sea glass. An example, a pair of blue earrings in genuine sea glass can cost $70+; in rare red colors they can sell for $200+. But a pair of Fanta Sea Glass earrings in similar colors and sizes cost about $25.

"Remember, it's very difficult to find genuine sea glass in colors, frosting, sizes and shapes that are suitably matched for use in earrings. That's certainly not a problem with craft glass".

This issue of craft glass disclosure was a big reason that Jereb, along with a sea glass dealer in California, founded the North American Sea Glass Association (NASGA) in 2005. Membership quickly expanded to include a group of authors and other sea glass dealers, along with numerous collectors. NASGA educates collectors and the general public about the characteristics and significance of genuine sea glass, provides commercial members with a code of business practice ethics, and emphasizes full disclosure on the craft glass issue.

Each year, NASGA hots a two day Sea Glass Festival, with lectures, seminars and exhibits by nationally known sea glass artisans, dealers, collectors, authors and photographers. The first two festivals were held in Santa Cruz, California. Nearly 2000 people attended the 2008 event, which was held October 11-12 in Lewes Delaware, just a ferry ride across the Delaware Bay from Cape May, New Jersey.

A highlight of the annual festival is the Shard of the Year Contest. A $1000 prize is awarded to the collector who enters the rarest and most desirable piece of sea glass. The contest is judged by NASGA board members and now draws some 900 entries each year. The 2007 winner was Kathleen Jones of Colorado, who entered a large, well frosted, bright orange piece with deep surface hydration and alteration.

"Nearly a third of these contest entries are exceptional pieces," Jereb says. "And that shows how much top quality sea glass in still being found on beaches".

Yet, the supply of sea glass is declining for several reasons. The first is that the extent of our beaches, the only places to collect sea glass, is finite. Secondly, with the growing population and soaring recreational uses of beaches, collecting pressure in increasing rapidly.

Other factors also contribute to the declining sea glass supply. Since the 1960s, plastics, and is some cases aluminum, have steadily replaces glass in everything from automobile lights to containers for food, alcoholic beverages, soft drinks, medicines and household commodities. Also, concerns about environmental protection have resulted in glass recycling, reduced littering, and more trash collection facilities. Accordingly, in recent decades less glass litter - the origin of sea glass - has gone into the sea sand environment. Other influences are the municipalities that rake beach sand to clean it, and the "re-nourishment" programs of dredging sand onto beached to compensate for erosion.

"Together, this paints a classic picture of decreasing supply and increasing demand" Jereb notes. "Sea glass prices have more than doubled in the past 10 years, and I expect them to double again in the next 10 years. Genuine sea glass was once sold by the pound or in large lots, but today it is more often sold by the individual piece".